‘We Don’t Watch the Bears in This House’

A Thanksgiving Story About Growing Up as a Bears Fan in a Packers Household

Believe it or not, a time exists when just being a professional football player didn’t provide enough annual income to pay the bills. It wasn’t very long ago, either. Before the NFL Players Association earned recognition in 1970, only the league’s superstars made significant money, if you want to call it that. Football as a career didn’t begin to emerge until the NFLPA demanded – and won – a league-minimum salary of $9,000 per year starting with the 1971 season.

My dad made a living keeping professional athletes employed once a season ended.

My old man was a hustler by nature. He was born in Tupelo, Mississippi, in 1938, and after a tornado destroyed his family home, lived in a tent with his parents, two brothers, and two sisters in Fort Wayne, IN. His family slowly made their way to Chicago via temporary stops in Walnut Corners, Wooster, Koontz Lake, Chesterton, and East Chicago. He went to Calumet High and played football, graduating in 1958. He joined the Army in 1959 and lost an entire lung to cancer in 1961 while stationed in Germany. Pops then moved to the Marquette Park area of Chicago, married my mom in 1963, and I was born a year later.

Dad took a job with Prudential to support my mom and me and managed to hook on as a contractor with both the Cubs and the Blackhawks, working as a financial director. That’s a nice way of saying he found professional athletes part-time jobs in the offseason. He placed most of his clients into positions with the Teamster’s Union at McCormick Place, though some worked as welders, mechanics, or salesmen. Phillip Wrigley would pay my father a bonus for getting players just enough of a stipend where each wouldn’t quit baseball to pursue a higher-paying job in another profession. My dad and Ron Santo were great friends.

The old man met with George Halas several times to offer his services to the Bears. In addition to finding players off-season work, Dad handled things like annuities, life insurance, brokerage services, and retirement management. He was well-liked by the players, many of who would come to our house in Worth, IL, sit at the dining room table, and go over financial documents with my father. Halas didn’t want his players working when they could be training instead. In fact, Ted Karras, John Johnson, Bob Wetoska, and Rich Kreitling were Dad’s only NFL clients.

To put things in perspective, a $9,000 salary back in 1971 is worth about $65,000 today, which was hardly enough to support a family. Wetoska and Kreitling actually worked for my father, recruiting professional athletes from other cities to retain Dad’s services. Word got back to Halas, who threatened to sue my father. With that, the old man stopped representing NFL players and became an immediate Packers fan.

Chicago drafted Walter Payton in 1975, but it was the 1974 team that initially made me a Bears fan. Wally Chambers was my favorite player, but I also liked Jim Osborne, Doug Buffone, Allan Ellis, Waymond Bryant, Ike Hill, and Carl Garrett. I had nothing but utter contempt for Gary Huff and preferred that Bobby Douglass start at quarterback though Abe Gibron didn’t see eye-to-eye with me on that. Why should he have? I was 11 years old.

In those days, and for most of the 1970s, it was difficult to catch Bears’ home games on local television. That was because of the NFL’s blackout rule. I think it still exists, at least in some iteration. Basically, if a home team didn’t sell out its game by Thursday, it was blacked out locally. We’d get the Packers or Vikings games instead, unless, of course, they played in Chicago. That was fine with Dad, who hated Halas.

“We don’t watch the Bears in this house.”

When the Bears played away games, we did chores instead of watching football. The lone exception was when the Jets played. My dad was a big fan of Joe Namath and Don Maynard. Maynard might be the only player who has played for three New York teams. He played for the Giants, the Jets, and the Titans (formerly the Jets).

My dad also used to collect matchbook covers. His favorites came from New York City, hence the affinity for Namath and the Jets. I loved that they had phone numbers that started with two letters. Oh for the days of rotary telephones.

“Billy’s Bungalow. 120 East 16th Street. GR3-7676.”

An aside: Our home phone number spelled out PROTECT, and my dad announced it as “Prospect 6-8328.” Security companies and law firms used to call us asking Mom or Dad to sell the number for something like $50 or $100 dollars.

Anyway, back to Dad’s matchbooks. He actually displayed them in these elaborate vases like they were Picassos or Rembrandts. The old man had to quit smoking when he lost his lung but he sure loved those matchbooks.

I used to think the matchbook collection was proof that our dominating achievement as human beings is simply to take up space while gathering meaningless tokens to remind us of meaningless things. I mean I had a marble collection for the love of Mike. You could get 400 for a buck back then so it was an inexpensive hobby. Hell, I’d find that in the sofa cushions on the mornings after Dad’s poker parties. I also learned to like the taste of warm Schlitz beer. Yes, I sampled the backwash in cans left overnight on our Formica countertops.

Dad’s athlete friends taught me how to pitch quarters. We called them “chucks” but the athletes called them “bread crumbs,” an obvious swipe at their bosses. I also learned how to play bar dice. I had such a well-rounded, financial upbringing.

When the Bears drafted Payton, the team was still a hard sell to Chicagoans. It almost seems impossible, being that Chicago is a die-hard football town. Number 34 almost pushed my dad to the Darkside, but he still couldn’t bear the thought of putting a single dollar into Halas’ wallet. The old man respected the hell out of Payton’s work ethic, and how could he not? We STILL couldn’t watch the Bears, though. My dad did give me an old GE transistor radio, however, so I could listen to the games while I raked leaves or shoveled snow.

By the time I was 13, I had a seven-inch black and white TV in my bedroom that I used to watch Indiana Hoosier basketball, plus the Cubs and Blackhawks games. On Sundays, I’d sneak into my bedroom to catch the exploits of Payton and Roland Harper, and though the Bears eventually made the playoffs in 1977, most home games were still blacked out due to a lack of fan interest. If Dad caught me watching, I’d be disciplined.

“We don’t watch the Bears in this house.”

Remember how Payton would do those gravity-defying leaps to get into the end zone? I’d mimic the great running back, bolting across my bedroom and leaping as high as I could before crashing down onto my bed. When Payton died on November 1, 1999, I was 35 years old. I did my touchdown leap one last time, dislocating my shoulder. I also went out to the backyard with my football and ran plays against an imaginary defense. There I was stiff-arming and high-stepping my way into the end zone, just like Walter.

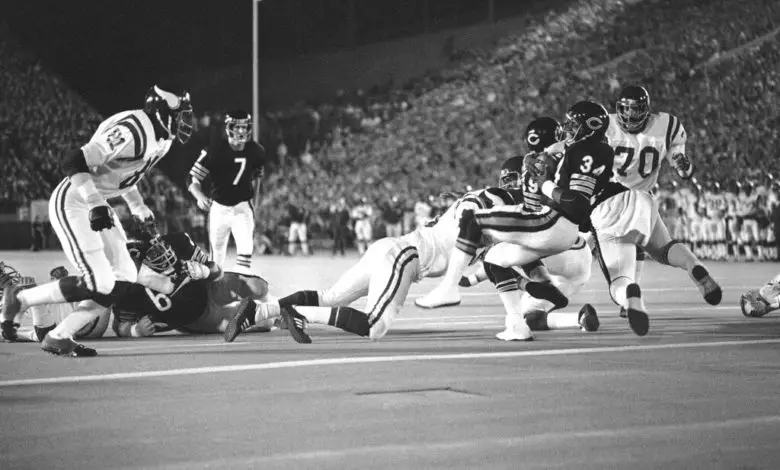

#OTD in 1977, a flu-ridden Walter Payton set the then NFL record for rushing yards in a game with 275 against Minnesota at Soldier Field.

It was the original “Flu Game.”

? @NFLonCBS pic.twitter.com/zegvJBOd3k

— Pro Football Hall of Fame (@ProFootballHOF) November 20, 2022

Payton broke the single-game rushing record on November 20, 1977. He ran for 275 yards in a game he played with a high fever and flu-like conditions. Payton wasn’t Chicago’s only sick player. Most of the team had the flu, and Buffone was hospitalized with viral pneumonia that week. He literally walked out of a hospital bed and onto the field.

I think the game was blacked out in Chicago, but my dad actually wanted to watch it. He was dying of cancer at the time. He was scheduled to have brain surgery a couple of weeks later, though I did not know. We drove to a tavern in Oak Lawn to watch the game. The bar had a high enough TV antenna that allowed it get the out-of-town feed.

Or maybe Dad just wanted to get out of the house so he wouldn’t break his own rule.

I sat there with my dad, drinking kiddie cocktails while he nursed a single Schlitz for the entire game. Payton ran sweep after sweep, destroying Vikings defenders in a 10-7 win. My father watched a Bears game with me and I was in shock, but I loved the bonding moment.

“I thought we don’t watch the Bears?” I asked as we pulled up to the bar.

“We don’t watch the Bears in my house.”